Globally or locally, seeds connect us to new generations

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault, in Norway, serves as a last resort and duplicate source for seed samples from around the world.(Svalbard Global Seed Vault)

BY LISA MARUN

(This article originally appeared in the October 8, 2022 edition of the San Diego Union-Tribune)

From seed vaults to neighborhood seed libraries, there is a wide range of scopes, methods and locations for ensuring that the world’s plant species are viable into the future. Seed banks and seed libraries have different roles; both are valuable assets toward the preservation of seeds for future generations.

At one end of the spectrum lie large, formal seed banks, of which there are over 10,000 worldwide. Seed banks or vaults are institutions, generally managed by universities, governments or nonprofits, where seeds are preserved for posterity. Most countries have at least one national seed bank, and there are also specialized seed banks for plants that are agricultural, wild, rare and/or for research.

The world’s largest seed repository was established by the Norwegian government in 2008. Nested in permafrost and locked in bomb- and disaster-protection structures, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault is aptly named the Doomsday Vault, for its purpose is to serve as a last resort and duplicate source for samples from seed collections around the world.

Seed stewardship

While institutional seed banks have important conservation, research and insurance purposes on a national and global level, most of these repositories hold redundant stores of seeds that are already under stewardship in ways that are citizen-led, local or both.

Aside from specific research or genetic conservation purposes, seeds generally hold their greatest value at a local scale. Collecting, planting and saving seeds from locally grown plants have been a part of human history long before formal seed banks appeared. Many Indigenous cultures today continue to maintain genetic and cultural legacies that live in the crops they grow from heirloom seeds, some of which are also now housed at the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

One such example is Seed Savers Exchange, which has been on a mission to protect the diversity of America’s endangered food crop and garden seeds since 1975. As the largest network of gardeners of its kind, this nongovernmental organization educates members and aims to preserve, distribute and share over 20,000 varieties of open-pollinated heirloom seeds. As with many government-based seed banks, food security, genetic preservation, and disease resistance are at the root of Seed Savers Exchange’s seed diversity and conservation goals.

Closer to home, with a different focus in terms of its conservation mission, is the Native Plant Seed Bank at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. Researchers there study native seeds, such as those of San Diego thornmint, with larger ecosystem preservation goals in mind, including improving coastal sage scrub habitat for a variety of plant and animal species.

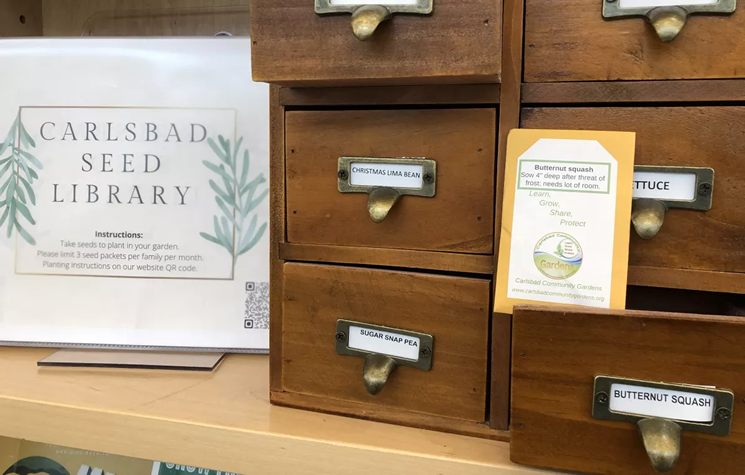

The Carlsbad City Library’s Seed Library is a free service for patrons that is supported by Carlsbad Community Gardens.(Lisa Marun)

Local seed libraries

San Diego residents have a plethora of ways to share seeds and connect with the community through local seed libraries without the need to become expert seed-savers. Seeds in seed libraries are contributed by the public for exchange and variety preservation. Along with garden clubs and community organizations, many San Diego Public Library locations offer seed libraries, as well as growing and harvesting resources and other garden-related workshops.

Also, like the hidden treasures that seeds themselves can be, there are many seed libraries that are hiding in plain sight. Free Flight, a nonprofit bird sanctuary in Del Mar, has recently partnered with the San Diego Audubon Society to support local backyard birds and pollinators by hosting a native seed library. And the WorldBeat Cultural Center, in Balboa Park, has incorporated a seed library into their services to support economic, environmental and public health programs.

DIY seed-saving

If your mission is to further explore the art and science of gardening by saving plant seeds, the process involves three steps: collection; drying and sorting; and packaging and labeling.

- First, collect the plant seeds once the seeds are mature for harvest. Seed maturity varies by plant, so check specifics for each plant.

- Next, dry and sort the seeds using the method that fits the plant type.

- Finally, carefully package your seeds in a moisture-resistant container with a label identifying your plant’s specific name, the collection date, and its planting and growing requirements.

Seeds come in all shapes and sizes, and can be collected, planted, and shared with others. Clockwise from top: milkweed (Asclepias incarnata); black-eyed Susan vine (Thumbergia alata); basil, Purple Petra (Ocimum basilicum); echinacea, Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea); and oregano (Origanum vulgare).(Lisa Marun)

Also, how do you dry and sort your seeds? For ripe fruits, you can scrape the seeds out and spread them on a cookie sheet in a warm, dark area until they dry and can be separated from fleshy attachments. For some flower heads, though, you can shake or pull seeds from their dried seed heads. Again, you may need drying and sorting guidance specific to your plant type to know what your best course of action is.

And while the packaging and labeling part of this process may seem straightforward, if you are growing multiple varieties of the same species, you will need to verify whether they tend to cross-pollinate and take measures to maintain seed purity and the integrity of your seed-saving procedures.

Regardless of your gardening experience, there are ample resources that will guide and empower you to become a super seed-saver, including a set of online tutorials for beginners provided by Seed Savers Exchange. For more information on seed-saving specifics, refer to the Union-Tribune August 2020 Garden Mastery article on seed saving.

From international seed safe-keeping in bomb-proof vaults to the practice of saving and sharing seeds with neighbors, collecting, preserving and growing from seeds benefits us all. It provides cultural and historical connections, a measure of food security and genetic diversity, and ways to conserve native ecosystems and to grow and eat locally.

Resources for growing from seeds and for finding seed libraries:

1. Master Gardener Association of San Diego County

2. “Community Seed Banks: How To Start A Seed Bank”

3. “Saving Seeds: Where to Start” (From Seed Savers Exchange)

4. Seed libraries at city of San Diego public libraries

Marun is a UCCE Master Gardener who believes the unique histories, beauty and potential of seeds adds an awe-inspiring dimension to the exploration of the complex world of plants.